In conjunction with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Sutton Avian Research Center supported a study on the status and ecology of Swainson’s Warbler in McCurtain County, Oklahoma. The warbler is now most common in the far southeastern tip of the state, although it has recently been documented in several areas of eastern Oklahoma. It long ago even nested in northern Washington County, not very far from the Sutton Center.

In conjunction with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Sutton Avian Research Center supported a study on the status and ecology of Swainson’s Warbler in McCurtain County, Oklahoma. The warbler is now most common in the far southeastern tip of the state, although it has recently been documented in several areas of eastern Oklahoma. It long ago even nested in northern Washington County, not very far from the Sutton Center.

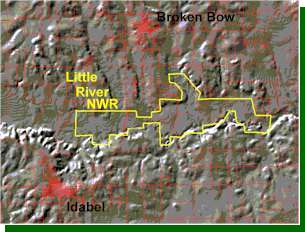

The Swainson’s Warbler surveys were primarily conducted on Little River National Wildlife Refuge, near Broken Bow, Oklahoma. Dr. Mia Revels has been studying Swainson’s Warblers for many years and shares her research story and insights into this little known species below.

The Swainson’s Warbler surveys were primarily conducted on Little River National Wildlife Refuge, near Broken Bow, Oklahoma. Dr. Mia Revels has been studying Swainson’s Warblers for many years and shares her research story and insights into this little known species below.

Living on the edge: Swainson’s Warblers in Oklahoma

By Dr. Mia Revels, Northeastern State University, Tahlequah, Oklahoma

I have been studying Swainson’s Warblers in Oklahoma for nearly twelve years and I am not tired of it yet. I honestly don’t think that I ever will be. Sure, the habitat can be tough – dense thickets full of ticks, mosquitoes, cottonmouths, poison ivy, and green briar. The weather gets pretty hot and humid by mid-July. But, to me, nothing is equal to the beauty of a bottomland forest in the spring time. The spider lilies and swamp irises in full bloom, the majestic cypress trees and water oaks, the sloughs and drainages that are home to so many creatures, the large rivers winding through the forest on their way to somewhere else, usually at a leisurely pace. And the Swainson’s Warblers and other birds! These wetlands are home to many species found nowhere else in the state.

Mia Revels prepares to capture a male Swainson’s Warbler using a decoy. Photo by Eric Enwall.

What is so special about Swainson’s Warblers? For one thing, they are very mysterious. Swainson’s Warblers are secretive birds. They spend most of their time foraging on the ground in dark, dense vegetation, and are rarely seen except by the most persistent of searchers. The easiest way to locate them is by listening for the male’s song, which is quite loud and carries for a long distance. Seeing them, however, usually requires entering their dark forest world. Males and females look similar, but can often be told apart by their behavior. Males arrive on the breeding grounds first and establish territories. Females arrive about a week later, choose a nest site, and build the nest alone. When people ask me where to look for Swainson’s Warblers nests, I tell them to look around for the place that they would most want to avoid in normal circumstances, and then go look there! Nests are located in the very densest locations in the male’s territory. Their nest is much larger and bulkier than other warblers, but the cup is normal sized. This unique nest structure makes identification of an inactive Swainson’s Warbler nest possible. After the eggs hatch, both parents feed the young birds. Once the nestlings fledge, both parents remain with them for several weeks, feeding and protecting them from predators.

The other thing that is special about Swainson’s Warblers is that they were once widespread in bottomland hardwood habitat throughout southeastern North America, but are now considered to be uncommon to rare across most of this range. One reason for this decline may be loss of breeding habitat caused by reservoir construction and conversion of bottomland hardwood forest to croplands, livestock grazing, and other purposes. Our remaining bottomland forests are precious resources and should be preserved and restored. Oklahoma’s Swainson’s Warblers are living on the edge – the western edge – of their range in North America.

Much of my work has been conducted on the Little River National Wildlife Refuge, as this is where Swainson’s Warblers are found in the largest numbers. I have also spent a considerable amount of time searching for other locations where Swainson’s Warblers might be found, mostly on public lands including Wildlife Management Areas and National Wildlife Refuges. This study was initiated by the Little River National Wildlife Refuge through the Sutton Avian Research Center when Berlin Heck was the refuge manager. He has since retired, but the work has gone on with the support of David Weaver, the current refuge manager. The project has been supported by other agencies including the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation, the University of Arkansas, and Northeastern State University. Individuals have also contributed, including many undergraduate students and other volunteers.

The main focus of the project was to determine the current abundance and distribution of Swainson’s Warblers in Oklahoma. Since they are a bottomland hardwood species, in Oklahoma that pretty much limits their potential distribution to the easternmost portion of the state. A history of the distribution of Swainson’s Warbler records prior to the initiation of this project is summarized by Berlin Heck (2001). In this study, I systematically searched for Swainson’s Warblers by driving, biking, hiking, paddling and crawling through appropriate habitat – all the while listening for song of a Swainson’s Warbler male on territory. If detected, a mist net was set up and a recorded Swainson’s Warbler song played under the net to attract the male in. Swainson’s Warbler models (painted artificial birds) were used to enhance the illusion that an intruder was present. My first model was a hand-painted, stuffed House Sparrow named Lenny Sweeney (a play on the scientific name Limnothlypis swainsonii). He didn’t hold up well in the field however, and had to be replaced by fake cardinals from the craft aisle that undergraduate students cut, carved, and painted to look remarkably like Swainson’s Warblers. Male Swainson’s Warblers are very territorial and usually respond quickly and aggressively to song playback and so are easily netted. Captured birds were banded with numbered aluminum USFWS bands. Twenty-seven Oklahoma Wildlife Management Areas and National Wildlife Refuges were surveyed. Swainson’s Warblers were detected in eleven of these, while the other 16 locations did not have suitable habitat for Swainson’s Warbler territories. Most of the new locations were previously unknown and are either relict populations or newly established ones.

Mia Revels shows off a model painted to resemble a Swainson’s Warbler. Photo by Dan L. Reinking.

I used radio-transmitters to investigate Swainson’s Warbler movements on their territories. Males were captured and transmitters super-glued onto their backs between the wings. Of five males, 1 experienced immediate transmitter failure, 1 left and never came back, and 3 were tracked extensively. I found that males have very patchy territories, sometimes composed of “islands” of forest separated by open shrubby field habitat, sloughs, or even rivers. Also, two of the tracked males left their territories immediately after fledging young. New males moved in within a few days afterward to make their own breeding attempt. This suggests that after successfully raising one brood, the family may begin their journey southward to their wintering grounds right away. So, I got some interesting information, and don’t worry – those transmitters fall off pretty quickly and I actually recovered two of them!

An important aspect of locating Swainson’s Warblers was documenting and describing the habitat where they were found. So, at the end of the breeding season, vegetation characteristics surrounding nest sites and within male territories were measured to determine habitat requirements for Swainson’s Warblers. Both were located in areas with dense, low canopy cover, a high stem count, and a ground cover that was mostly leaf litter. Nests were in areas that were the darkest and densest “pockets” of the male territories.

Mia Revels and James Waffle prepare to band a Swainson’s Warbler in the

understory below the forest canopy. Photo by Eric Enwall.

The earliest date that I found Swainson’s Warblers on the LRNWR varied from year to year with the earliest confirmed arrival date on April 7 in 2007. I banded 297 birds during the study. Of those, thirty-nine were recaptured in at least one year after they were first banded. Most recaptured males returned to the exact same territory where they were originally banded, sometimes in the exact same net lane! Three males were located on the same territory for four years in a row, 5 for three years in a row, and 11 for two years in a row. It seems that Swainson’s Warblers will continue to use the same territories year after year when possible.

All the habitat in the world is not going to help Swainson’s Warblers if they are not nesting successfully in that habitat. Figuring this out involves finding and monitoring nests in order to see if they are successful and if not, why. The first Swainson’s Warblers nests in Oklahoma were located by Albert J. B. Kirn in 1914 and 1917. Since then, no nests had been reported in Oklahoma prior to this study. The absence of nesting records reflects both the scarcity of Swainson’s Warblers and the difficulty of locating their nests. The nests of many birds can be located by using cues provided by the adult birds, but Swainson’s Warblers are difficult to see and follow through the dense vegetation that they inhabit. In fact, this habitat has been described as “impenetrable” by many researchers. In spite of all these obstacles, in 2001, I documented the first record of a Swainson’s Warbler nest in Oklahoma since 1917! There were no eggs in the nest, and no adults present. It looked like a large clump of leaves from the side, but viewed from the top contained a small, neat cup. On May 10, a female Swainson’s Warbler was on the nest, confirming my initial identification. When checked later that same day, the female was away and the nest contained 4 eggs. On 20 May the eggs hatched. Sadly, that first nest was eventually depredated before the nestlings fledged.

However, I located 71 more Swainson’s Warbler nests between 2001 and 2009. Thirty-one of these were both active and monitored to conclusion to determine their fate. Of these, 19% were abandoned, 48% were depredated, and 32% were successful. In two cases, abandonment was related to a violent storm in 2002 which caused the nests to come dislodged from the cane they were placed in and the eggs and nestlings fell to the ground. In two other cases, abandonment occurred after Brown-headed Cowbird parasitism. In the last two cases, the cause was unknown. The 32% of nests that were successful fledged at least one nestling.

Swainson’s Warbler on a nest. Photo by Mia Revels.

Another potential cause of reduced nest success in Swainson’s Warblers is Brown-headed Cowbird parasitism. Cowbirds are brood parasites that do not build their own nests, but instead lay their own eggs in other bird’s nests. These hosts raise the young cowbirds, reducing their own reproductive success. Cowbird nestlings are larger and more aggressive than the warbler nestlings and will often push the warbler nestlings out of the nest or crush them. Cowbird eggs or nestlings were found in 17% of active Swainson’s Warbler nests. Of the parasitized nests whose fates were known, 33% were abandoned. Two parasitized nests were successful because the cowbird egg never hatched. Two nests containing cowbird nestlings were depredated, allowing the adults to renest.

So, how can we help the Swainson’s Warbler in Oklahoma? In areas with good habitat that harbor large numbers of this species, little to no management is needed. In areas where they occur in small numbers, the main thing that will benefit them is habitat regeneration or restoration. Riparian forest, in particular, should be restored. In many surveyed areas, the riparian forest corridor was very narrow, or in some cases, totally absent. Whenever possible, efforts should focus on maintaining or restoring giant river cane, which seems to be the preferred nesting substrate for Swainson’s Warblers.

I am finishing writing this article just as I am getting ready to go back to the LRNWR and reexamine the population there. I have to dig out my nets, poles, models, GPS unit and other equipment and get down there in time to find that first Swainson’s Warbler of the year. When I hear that first song my heart will race and I will charge into the thicket to see if he is already banded or a new male that will be wearing one before I release him once again to spend his summer foraging, attracting a mate, and hopefully –raising a new brood of Swainson’s Warblers.

Swainson’s Warbler ready to be released. Photo by Eric Enwall.