The George M. Sutton Avian Research Center was named after George Miksch Sutton (1898-1982), who until his death served as Professor Emeritus at the University of Oklahoma and as an example to all aspiring field ornithologists. Who’s Who gives a thorough account of this “most prominent ornithologist of his time.” A recently-published bibliography of his works lists 13 books, 18 monographs and museum publications, 201 journal articles, 12 book reviews, four obituaries, 18 popular articles and eight essays. He also illustrated at least another 18 books. As “Doc” was so intensely interested in hands-on studies of birds in the field, we felt it most fitting to commemorate this dedicated individual by naming the research center after him.

Dr. Jerome Jackson authored a biography of Sutton, published by University of Oklahoma Press in 2007. A short biography appears below.

An Eye for Birds — The Life of George Miksch Sutton

by Jerome A. Jackson

George Miksch Sutton was born in Bethany, Nebraska, on 16 May 1898. He was the only son and oldest child of Harry Trumbull Sutton and Lola Anna Mix Sutton. We know of Doc (as he was known to all who knew him) as a result of his art, his ornithology, his popular writings, his philanthropy, and for some lucky ones among us, his friendship. To better understand the man that George became, it helps to know his parents and of his youth. George wrote of his youth in his autobiography, Bird Student (1980, Univ. Oklahoma Press), but many of the details included there are recollections that are not completely accurate. In the course of preparing a more detailed biography of Sutton, I have ferreted out many new details. In the paragraphs that follow I share only a brief glimpse of this man: George Miksch Sutton.

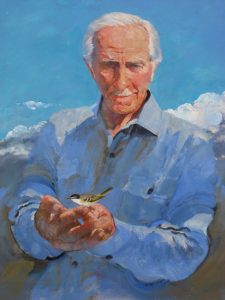

“George Miksch Sutton” by Robert Heindel (1938-2005)

Harry Trumbull Sutton was a minister and a teacher at Cotner College in Bethany when George was born — the chairman of the Department of Eloquence, a wonderful name that at any college today would be the “Department of Speech” or “Communications.” But “Eloquence” was befitting the times and the man. Harry was a master at recitation of the works of Shakespeare and frequently travelled to perform his recitations as well as to preach at various churches. In 1906, Harry ran for governor of Nebraska on the Prohibition ticket, though he lost by a considerable margin. His wife, Lola Anna Mix, was of Moravian ancestry. She had been born Lola Anna Miksch, but when her family moved to Minnesota during her teens, her father changed the family name to its phonetic spelling “Mix” in order to better fit in. Although she used the name “Mix” during her tenure at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, she never really approved of the change. To perpetuate the family name, she gave each of her children the middle name”Miksch.” Harry and Lola had travelled with the Chautauqua program in the 1890s, Harry lecturing and Lola leading songs and playing the piano. Lola was 30 when they settled down in Bethany and George was born. Throughout her life she taught music and occasionally English. George certainly came to share his father’s eloquence and his mother’s love of music.

One of the most influential features of George’s childhood was that his family moved frequently. In 1901 they moved to Aitkin, Minnesota. By 1903, they were back in Bethany, Nebraska. Around 1907 they moved to Ashland, Oregon, and shortly after that, to Eugene, Oregon. A year later they were in Eureka, Illinois. In 1910, his parents split up while his mother studied music in Chicago. For a year, George and his sisters were separated, George living with his grandparents in Winnebago, Minnesota. In 1911, the family was back in Illinois, then moved to Ft. Worth, Texas, and by 1914 had moved to Bethany, West Virginia. The positive sides of this itinerant youth were that George saw America and learned much about regional differences and similarities in habitats and birds, that he was quite close to his family, and that he became incredibly self-reliant. The negative side was that George had little opportunity to establish long-term friendships with other children or his teachers.

Birds were the threads that provided continuity through his childhood. At the age of five his parents gave him Frank Chapman’s book Bird-Life. At the age of 10 he corresponded with a journal editor about his observations of swallows catching feathers. At age 11 he got his first bird-skinning lessons. At age 12 his first bird drawing (of an oriole at its nest) was published, and George joined the American Ornithologists’ Union. At age 13, George took mail order taxidermy lessons from the Northwestern School of Taxidermy in Omaha, and was keeping a menagerie of birds and mammals –including a skunk– and was attending classes as a special high school student at Texas Christian University. By age 16, George had published articles in The Oologist and Bird-Lore.

Jerome Jackson detailed the life of his mentor “Doc” Sutton in his 2007 biography

In 1915, George began corresponding with the famed bird artist, Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Fuertes responded with kindness and constructive criticism. This was exactly the stimulus that he needed; he was on the path he had been seeking. During late summer of 1916, George traveled by train to spend a few weeks with Fuertes. Although he painted no birds while he was there, the experience was crucial.

In 1918, George began work at the Carnegie Museum, at first in charge of the egg collection, but later accompanying W.E.C. Todd on field expeditions to Labrador and the far north. Although he was to have graduated with a Bachelor’s degree from Bethany College in Bethany, West Virginia, in 1919, he was expelled instead — for leading a student revolt against mandatory ROTC training at the college. In 1923 he was allowed to finish his work there and finally graduated.

In 1925 George left Carnegie to become State Ornithologist for Pennsylvania, a position from which he defended birds of prey to sportsmen and which included travel throughout the state. This work ultimately resulted in his first book, An Introduction to the Birds of Pennsylvania (1928). George quit his job as State Ornithologist in 1929 in order to begin graduate research for the Ph.D. under Arthur Allen of Cornell University. He left Pennsylvania in the summer of 1929 to spend a year on Southampton Island in the Canadian Arctic. On his return, he settled in at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, to complete course work and his dissertation. It was there that he met and became a lifelong friend of Sewall Pettingill. Following graduate school, Doc remained at Cornell as Curator of Birds, travelling frequently to collect specimens and to paint. He maintained his ties with Carnegie, joining further expeditions to the Arctic, Texas, and Mexico. During these years he also wrote two books, Eskimo Year (1934) and Birds in the Wilderness (1936), and illustrated several others. Although employed at Cornell, Doc developed close ties with Joselyn Van Tyne at the University of Michigan, spent summers working at the University of Michigan field station, and sought a position at the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. When one was finally offered, he chose to stay at Cornell.

With the outbreak of World War II, Doc felt obliged to enlist. He inquired of opportunities in both the Navy and Army and was finally enlisted in the Army Air Corps to test Arctic survival gear. While stationed at various bases in North America, Doc continued painting birds and writing for both professional and popular audiences. He rose to the rank of Major shortly before he was discharged with undulant fever. While in the Army Air Corps, Sutton birded with other Army ornithologists such as Sergeant Roger Tory Peterson and Lieutenant Franklin McCamey. Peterson once told me that he could never think of Sutton without thinking “Sir.” Following the War, Doc got another offer of employment at the University of Michigan and this time he took it.

Another book, Mexican Birds: First Impressions, appeared in 1951. This book elaborated on articles he had published in Audubon Magazine during the 1940s and stimulated further work that ultimately led to the establishment of the Rancho de Cielo field station.

Unfortunately, the long sought position at Michigan didn’t work out to his liking — apparently in part due to a personality conflict with Van Tyne. At a distance they had become good friends; being close destroyed that friendship. Doc began looking for employment elsewhere. He wanted a full-time faculty position.

Sutton produced many books about his research travels, including a summer on Iceland.

In the summer of 1951, Doc taught at the University of Oklahoma Biological Station and established contacts that led, in 1952, to a position as Professor of Zoology at the University of Oklahoma. The same year, Doc was awarded an honorary doctorate from Bethany College. Doc and his friend Sewall Pettingill, along with Sewall’s wife, Eleanor, spent the summer of 1958 in Iceland. It was a grand adventure that resulted in Doc’s book Iceland Summer. One of the paintings Doc created, of a Gyrfalcon on a ledge, was used in preparing an Icelandic postage stamp. For his book and artwork focusing on Iceland, George Miksch Sutton became “Sir George Miksch Sutton” when he was awarded the Knight Cross Order of the Falcon by the Icelandic government in 1972.

Sutton’s book, Oklahoma Birds (1967), came as culmination of a long effort that had stimulated ornithological research throughout the state. Although Doc officially retired from the University of Oklahoma in 1968, he remained as Curator of Birds at the Stovall Museum and as George Lynn Cross Research Professor Emeritus. He also continued to work with graduate students, to paint, and to write.

More books appeared: in 1971, High Arctic; in 1972, At a Bend in a Mexican River; in 1975, Portraits of Mexican Birds; and in 1977, Fifty Common Birds of Oklahoma and the Southern Great Plains. In 1977 he was named “Master Wildlife Artist” by the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Museum in Wisconsin. In 1979, Doc published his correspondence with Louis Agassiz Fuertes in To a Young Bird Artist — a book that should be must reading for any aspiring bird artist. Throughout his life George Sutton was a bridge between birds and people and between amateur birders and professional ornithologists. His artwork illustrated many books and the covers of several journals. These included longtime cover illustrations for the cover of the Sewickley Valley Audubon Society journal, The Cardinal; for the Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union journal, Nebraska Bird Review; and for the Wilson Bulletin (two different covers). Early in his professional life he committed himself to supporting professional ornithology and he was especially supportive of the Wilson Ornithological Society. In addition to his cover illustrations, Doc served as President of the Society, and later as Editor of the Wilson Bulletin. He contributed many color plates and other illustrations to that journal and in 1972 donated funds to establish the Sutton Color Plate Fund to assure that there could be a color plate in each issue of the Wilson Bulletin. Doc also nourished the Oklahoma Ornithological Society with funds, artwork, his expertise and enthusiasm.

Over the years Doc’s art evolved from illustration of birds to illustration of birds in their habitats. He sought recognition as a fine artist, not merely as an illustrator of birds. In my opinion his later art, as exemplified in High Arctic, made him deserving of that recognition. Sutton was a master with pen and ink and with watercolor. His paintings of baby birds are especially exciting. He knew birds; he knew his medium; he understood light.

Although Doc didn’t like to sell his paintings, when there was a need, he was there. His art helped raise funds for Rancho de Cielo, for the Oklahoma City Zoo, for scholarships at the University of Oklahoma, for a diorama at the University of Minnesota Museum of Natural History, for the purchase of a grand piano at the University of Oklahoma, for funds to assist a friend with cancer, and many other causes. Following a long bout with prostate cancer, George Miksch Sutton died on 7 December 1982. Heeding his wishes, friends took his ashes to the Black Mesa country of western Oklahoma, where they were dispersed by the wind among the birds and habitats he loved so much.

It is not surprising that Doc left behind a number of manuscripts as contributions to the Bulletin of the Oklahoma Ornithological Society, and that his many friends saw to it that his last book, Birds Worth Watching (1986), was brought to fruition.

— Jerome A. Jackson is Whitaker Eminent Scholar and Professor at Florida Gulf Coast University. His biography of George Miksch Sutton was published by the University of Oklahoma Press in April 2007.

Presentation video on George Sutton below.